Lately, for whatever reason, I’ve been spinning a lot of Cheap Trick records. After a few more purchases, I’ll be content with having enough C.T. titles in the collection (maybe In Color, definitely Dream Police and perhaps One On One). That is, unless Cheap Trick throws down another required listening effort, which is quite possible because they’re still going at it and they seem to be undergoing a creative resurgence, if I’m judging their latest Rockford correctly; it’s as good as they’ve done in nearly twenty years and, unlike the solid (yet horribly overproduced and dated One On One), it bypasses any attempt at “updating” their sound and relinquishes modernism for focusing on what made ‘em Rockford, Illinois finest rock and roll export.

What seems to be getting continual listens is Cheap Trick’s debut album, the remastered version with bonus tracks (including a rough demo of “I Want You To Want Me” that is totally better than the one on In Color). I’ve tried to imagine what the hell people thought of this album at the time it was released; quirky, hooky, and rough in the right places, it was unlike anything else in 1977, yet today its influence is obvious.

With songs about pedophiles, mass murderers, suicide, and greed, it’s understandable why Cheap Trick struggled a hair above obscurity while their wonderful power chords and Beatles-esque sense of melody made it easy to understand why a major label like Epic continued to foster the band along, hoping that the audience would eventually catch on.

They did, of course, with the absolutely essential Live At Budokan. The reality is that Budokan merely captures the environment that was the band’s bread and butter until record buyers had a chance to catch up: their live show. And while, with the exception of the debut, their recorded studio output found the band exploring various directions (oftentimes with frustrating results), Live At Budokan documents a band quite confident and agile on stage.

What it doesn’t do (and this doesn’t distract from how awesome that album is) is capture the characters that made up the band, during a time in rock in which lasting impressions were sometimes critical to a band’s success.

That was best experienced by seeing Cheap Trick live.

During the tour for All Shook Up, the band made their way to Memorial Auditorium, a small arena nestled on the banks of the Mississippi River in Burlington, Iowa. The venue is a stopping point for bands reaching the end of their apex, and in some cases, bands that are on the verge of stardom (Guns ‘N Roses and Metallica played there just before their careers took off).

As evidenced by Mike Damone’s struggles to unload C.T. tickets to a young customer in Fast Times at Ridgemont High, the band was experiencing smaller than normal venues and less than expected record sales. Yet these Midwestern favorites continued to be a draw in Southeast Iowa and I got a friend excited about taking the 45 minute long trek to see his first concert.

Our seats were in the first ten rows, which probably created a strong memory for my friend. After all, you could do worse, much worse actually, than having Cheap Trick as your first live experience.

The other thing that probably created a strong memory was the selection of great material they played for this tour. Road tested to the point where they could probably play the entire set in their sleep, the band showed no evidence of disappointment that they were playing a date in a town that’s highest population figure was probably a generous 45,000 residents.

Rick Nielsen provided the crowd with the obligatory in-between song stage banter and in-song guitar pick tossing, one of which ended up on the floor directly in front of my friend’s seat. It’s a souvenir that I hope he still has to this day.

Nielsen used his checkerboard Hamer Explorer guitar throughout most of the performance, until he brought out the Hamer 5 neck out for a money shot.

Bun E. Carlos stayed in back most of the night, smoking and drumming, until something drew his attention from the drum riser.

“You….look…great!” Nielsen said.

“We…feel….great!” he continued.

Then, someone from the crowd through a joint on stage, which landed near Rick. Carlos, having noticed this offering, got up from his kit and walked towards the front of the stage by Rick. Nielsen noticed and then offered “Bun E….feels….great!”

Carlos picked up the joint and drew a lighter from his pocket. He lit the joint and took a large hit, much to the delight of the crowd.

“Bun E……feels….greater!”

He took another hit, and holding the smoke in his lungs, he grabbed the microphone from Rick and gave the crowd his opinion of the gift.

“Good shit.” He said, before handing the joint to someone in the front row and returning back to the drum kit.

For a fifteen year old kid, it was one of the most awesome things I had ever seen and it forever changed my opinion of Bun E. Carlos.

But time, weed, and the introduction of outside songwriters faded the image of this concert from my memory, and Cheap Trick became “street fair” act. I’m fairly certain that the band really couldn’t care less about what me, or anybody else thought about their tour schedule. They were doing what they set out to do all along: make a living playing original rock and roll music.

So with each tour, they play the obligatory hits package and incorporate a few new tracks to promote their latest effort. The thing is, having seen the band play “Surrender,” “I Want You To Want Me,” and other catalog favorites countless times, they don’t seem to be any less enthused about performing them today than when they were new.

So while newer bands underscore what they feel they’re “entitled” to, Cheap Trick understands they the only entitlement they have is showing up to the 150-200 shows they book each year. The stage has always been their strong point, and we’re privileged that they’re still at it, no matter what stage they decide to walk on.

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Iron Maiden-A Matter Of Life And Death

True story: I was driving around with the little dude in the car seat, listening to Iron Maiden’s Killers. The song that grabbed his attention was “Wrathchild,” which he thought was pronounced “rockchild” because he understood the track is pretty rockin’. So he’s doing the obligatory head-nodding, throwing up the horns like I taught him, and trying to get my attention in the rear view mirror buy saying “Look at me! I’m a wrathchild!” It was one of those bonding moments that make you think the kid will turn out all right.

True story: I was driving around with the little dude in the car seat, listening to Iron Maiden’s Killers. The song that grabbed his attention was “Wrathchild,” which he thought was pronounced “rockchild” because he understood the track is pretty rockin’. So he’s doing the obligatory head-nodding, throwing up the horns like I taught him, and trying to get my attention in the rear view mirror buy saying “Look at me! I’m a wrathchild!” It was one of those bonding moments that make you think the kid will turn out all right.Later on, we were watching “Full House” together (his choice, he has a thing for toddler-era Olsen twins) when John Stamos appeared in a scene. Stamos was dressed in black, had an electric guitar and that silly looking mane on his head, which prompted the little one to declare “He’s a rockchild too, Daddy.” I had to correct him, of course, because there’s a huge difference between Iron Maiden and John Stamos.

I’ll admit to not following Maiden too closely for quite some time; I lost track of them during my obligatory “purge everything metal” phase, which I’ve thankfully realized was a completely stupid thing on my part as I’ve come to terms with my metal influences. Maiden was one of them, of course, but by the time I reconciled with the genre, Maiden had replaced vocalist Bruce Dickenson and who wants that?

Two albums ago, the rest of the band brought Dickenson back and guitarist Adrian Smith, providing fans with a reunion of the classic Maiden line-up of the 80’s. But riding a wave of nostalgia is not the sort of thing that the band is apparently content on doing. Their latest release, A Matter Of Life And Death, finds the band forging ahead while keeping their enormous influence and bravado completely in tact. It’s reassuring that this, their fourteenth album, not only manages to complement their existing catalog but also add some range to it.

The opening track, “A Different World,” is a great example of this. Leading with that famous Maiden trademark sound, the song begins by focusing on those who are unwilling to change and unhappy that they can’t stop change from happening. The song then suddenly opens into a wonderful, lower register chorus, preaching tolerance (“tell me what you can hear/and then tell me what you see/everybody has a different way to view the world”) without the use of Dickenson’s famous operatic vocal scalings.

It’s also the shortest track, clocking in at a hair over four minutes. The rest of the album approaches epic qualities with three tracks going over the eight minute mark, four over seven, and the rest over five; like the Iron Maiden of old, there is a slim chance that any of the songs will be provided commercial exposure.

A Matter Of Life And Death feels like a looser effort than albums past. Drummer Nicko McBrain limits the fills and focuses more on playing in the pocket while the band’s three(!) guitar attack is clearly defined and fluid, including some acoustic flourishes that appear on a few of the songs. Surprisingly, the band seems to have made an album that was conceived, recorded, and released fairly quickly. This approach works for them; Maiden has been at this thing long enough that they can be tight without the help of studio gadgets and obsessive perfectionists manning the control room. I’m looking at you, Bob Rock.

There will be a few fans that miss the operatic bombast of Dickenson’s voice on every track, and they may be a little dismayed at a more progressive rock direction the band appears to be taking with this release. The reality is that Maiden have has some progressive tendencies in their leather armbands. Now they seem comfortable enough to demonstrate it rather than roll over them like they’ve already perfected.

A Matter Of Life And Death won’t be the album that gets you to suddenly appreciate Iron Maiden (you get them or you don’t) and it’s not the “return to form” album that existing fans probably want them to make. In their minds, they’ve made those records and you’re welcomed to pick them up (The Number Of The Beast, Piece Of Mind and Powerslave are where you should start) and watch them prove their worthiness in a live setting where, apparently, they still have the ability to rule. Instead, it’s a very credible example of a band that understands if they’re content with simply holding on to nostalgia, they’re as good as dead. Or Ed, as the case may be.

This review originally appeared in Glorious Noise

Monday, November 13, 2006

Boris-Pink

Godzilla, a prehistoric monster rudely awaken by American atom bomb testing in the Pacific Ocean, should not be confused with the band Boris, a rock monster rudely awaken by sludge/psychedelic/noise music that traveled across the Pacific Ocean from America. It’s easy to understand the confusion; however, as both beasts can level buildings in their path and both possess thermonuclear breath.

Godzilla, a prehistoric monster rudely awaken by American atom bomb testing in the Pacific Ocean, should not be confused with the band Boris, a rock monster rudely awaken by sludge/psychedelic/noise music that traveled across the Pacific Ocean from America. It’s easy to understand the confusion; however, as both beasts can level buildings in their path and both possess thermonuclear breath.Originally released in Japan last year, Boris’ Pink is, I’m guessing here, their 16th album (not counting live albums and comps) in the past decade, and probably their most comprehensive: every hard rock genre twist that Boris has managed throughout their career can be found here, in one tinnitus-inducing 45 minute package.

Elements of The Stooges, Kyuss, Melvins and any other band that finds solace in decimating amplifiers is represented. The only thing that seems to be holding the leash is the confines of the v.u. meter, which is buried red deep throughout the majority of the album.

This is supposed to be their most accessible effort to date; which, of course, is a hoot because every track (aside from the instrumentals) is sung in Japanese and, even then, is somewhat irrelevant as any semblance of vocals is usually crucified at the hands of the unrelenting guitar grind.

While labelmates Sunn 0))) steadfastly study the art of metallic drone, Boris nicely summarizes several areas of metal with the attention span of a Ritalin-enabled video gamer. And like the most devoted player, this power trio has completed all of the levels without the aid of cheat codes; there’s absolute passion in their performances and a great deal of hard work behind that wall of din.

Oh no, there goes Tokyo…

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Upstairs At Eric's In Southeastern Iowa

It’s easier today to find new music, new artists, and become the obligatory small town music snob. At least that’s my perception. The funky cold medena known as the internets is a boon for those teens that check in daily to Pitchfork to learn that there’s a band called Rainer Maria and that the band Rainer Maria recently broke up. The teen can then go to school and weep to all of his/her emo friends that the best band since Pinkerton was released is no longer with us.

There was a time when musical elitism was passed through direct contact. Word of mouth was huge, as was the Maxell XL-II C-90 cassette. For whatever reason, I can specifically remember how one band made inroads in a small town Iowa community.

What makes this story unusual is the style of the band in question, the socio-economic make-up of the community, and the manner in which the musical penetration occurred.

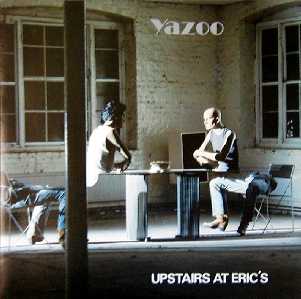

The band was Yaz (known in England as Yazoo) and the album (actually in the form of a cassette) was called Upstairs At Eric’s. It was the summer of 1983, probably a full year after the album was actually issued.

Some background: Yaz was a British electronic band consisting of Alison Moyet on lead vocals and Vince Clarke on synthesizers. Moyet had/has a very rich, deep female alto which was a strange juxtaposition against Clarke’s cold keyboards. Clarke, who was involved in a relationship with Moyet during Yaz’s heyday, had recently left Depeche Mode who had found initial success with their album Speak & Spell. I had never heard of Depeche Mode, and I’m sure that many others in my town hadn’t either; Yaz’s sound was fairly reminiscent of them, but in the confines of a duo, Moyet and Clarke’s sound was sparse and dark with the occasional foray into dance music. Of course, I didn’t know this at the time.

One of my friends had the privilege of having a swimming pool at his home and an even greater privilege of having parent’s that entrusted him with taking care of himself. This glorious lack of parental supervision created a climate in which poor judgment, the illegal consumption of alcohol, and a comfortable area to congregate became commonplace among people in the same age group.

On one such occasion, we gathered on a warm June evening for an impromptu poolside party.

One attendee, a tall, pale fair skinned girl with an even taller mop of red hair, joined the festivities with a girl who was either a relative or friend of hers that happened to be visiting our town from the uber-cool confines of the Northeast. The visitor, in either an attempt to act cool or because of “new kid shyness,” was fairly reserved with a hint of arrogance. To make matters worse: she was attractive. With no time to worry about such dramatics (after all, she’d be gone in a few days, way too little time to break down any perceived walls of conceitedness to get into her pants) she was included in the social environment and even provided the luxury of having a go at the boombox with her own selection. She went back to the redhead’s car and pulled out a cassette of Upstairs At Eric’s. We were probably listening to Pyromania or 1999, both great albums in their own right, but certainly nothing tremendously groundbreaking and certainly not very hip to someone within earshot of a low-wattage college station or similarly located dance club.

Within moments of the pecking, tart synths of “Don’t Go,” some heads turned to ask “What is this?” while the bolder musical snobs looked at the strangely positioned mannequins on the cassette cover of the album. When the album was over, we probably countered with something ridiculous like Frankie Goes To Hollywood, but no matter: some creative soul (perhaps myself or the host of the party) secretly “lost” the cassette with the obvious intention of not returning it. Thankfully, liquor has a strange effect like causing people to forget things like inhibitions, panties, and cassette tapes of Upstairs At Eric’s.

From there, the cassette found its way into the car stereo of my friend’s Pontiac Firebird, where the sonic effects of the music was met with the approval under the influence of marijuana. It became an issue of 1.) either we must conceal the fact that the tape was in our possession or 2.) we must find a dubbing cassette to make a copy before returning it to its rightful owner before she left to go back east.

The first answer was hard to deal with as the red haired friend called the following day to inquire on the whereabouts of the tape. I could truthfully delay the return of the cassette since it was still in the armrest of the Firebird and, since it was summer, it may be a few days to coordinate with the schedule of the friend and the redhead.

Actually, I saw my friend on a fairly regular schedule, and by Monday, I had the cassette back but not before he had made a shitty copy of it on his dual cassette boombox; fidelity, Dolby, and the added tape hiss was not an issue with him.

I then received a couple of phone calls from party-goers who wanted to know the name of the band and if they too could get a copy made for their own collection. One of these calls was from someone who had a dubbing cassette desk in his components that could transfer the noise-reduction and do it at double speed.

Three copies were made (mine, his, and a friend of his) and we were pleased with the results. The original was dutifully provided back to the redhead in time for her to return it to her friend before she left our small town and planted the seed of Yaz among its teenage citizens.

By the following weekend, I ran across two additional people who had made third generation copies of our own, diminishing the fidelity even more, but not the enthusiasm for this electronic duo.

Upstairs At Eric’s was a strange find, particularly for a town that typically preferred heavy metal and who’s main employer was various manufacturing plants that provided high school graduates with minimal intelligence and initiative with a decent paying job until the plants eventually shut down.

The metal kids were actually fairly receptive to Eric’s trippier tracks like “I Before E (Except After C)” and “In My Room.” The chicks liked the love songs like “Only You” and “Midnight.” And, of course, the gay kids who had yet come out of the closet preferred the dance tracks like “Situation” and “Bring Your Love Down (Didn’t I).” It remains a touchtone album for me and it remains one of the best examples of 80’s British electronica today.

It also served as a precursor to gay dance music (Bronski Beat, the Clarke led Erasure, Dead or Alive) which makes the dichotomy between my hometown makeup and the fan base of a lot of these types of bands quite amusing.

One curious footnote to Yaz: My Father only demanded that I remove two music selections during family car trips, thereby securing my understanding that the driver of the vehicle is in charge of all of the controls as well. One tape was Yes’ Drama (ironically, I brought this tape because I thought the Cream-lovin’ guy would like it. We got lost, he got frustrated, and he felt this album was “distracting.” It is a shitty album. But still, let’s place blame correctly.) and the other was Upstairs At Eric’s. He told me to “Turn that shit off!” When I persisted and wanted to know why, he told me it sounded like “A guy trying to sound like a girl with a bunch of synthesizers.”

“That is a girl, Dad!”

It didn’t matter; he turned the radio on and we listed to N.P.R. instead.

A few months later, I was down at the Disc Jockey record store and noticed a strange album cover on the new releases section. It was Yaz’s second and final album You And Me Both released just before Moyet and Clarke ended their relationship together. I picked up a copy and went up to the counter to pay for it. Standing in line ahead of me was the redhead who’s friend introduced a small town to the English electronica band Yaz. In her hand was her own copy of You And Me Both and in her head she was still probably oblivious to the domino effect her friend had on a small town in Iowa the summer before.

There was a time when musical elitism was passed through direct contact. Word of mouth was huge, as was the Maxell XL-II C-90 cassette. For whatever reason, I can specifically remember how one band made inroads in a small town Iowa community.

What makes this story unusual is the style of the band in question, the socio-economic make-up of the community, and the manner in which the musical penetration occurred.

The band was Yaz (known in England as Yazoo) and the album (actually in the form of a cassette) was called Upstairs At Eric’s. It was the summer of 1983, probably a full year after the album was actually issued.

Some background: Yaz was a British electronic band consisting of Alison Moyet on lead vocals and Vince Clarke on synthesizers. Moyet had/has a very rich, deep female alto which was a strange juxtaposition against Clarke’s cold keyboards. Clarke, who was involved in a relationship with Moyet during Yaz’s heyday, had recently left Depeche Mode who had found initial success with their album Speak & Spell. I had never heard of Depeche Mode, and I’m sure that many others in my town hadn’t either; Yaz’s sound was fairly reminiscent of them, but in the confines of a duo, Moyet and Clarke’s sound was sparse and dark with the occasional foray into dance music. Of course, I didn’t know this at the time.

One of my friends had the privilege of having a swimming pool at his home and an even greater privilege of having parent’s that entrusted him with taking care of himself. This glorious lack of parental supervision created a climate in which poor judgment, the illegal consumption of alcohol, and a comfortable area to congregate became commonplace among people in the same age group.

On one such occasion, we gathered on a warm June evening for an impromptu poolside party.

One attendee, a tall, pale fair skinned girl with an even taller mop of red hair, joined the festivities with a girl who was either a relative or friend of hers that happened to be visiting our town from the uber-cool confines of the Northeast. The visitor, in either an attempt to act cool or because of “new kid shyness,” was fairly reserved with a hint of arrogance. To make matters worse: she was attractive. With no time to worry about such dramatics (after all, she’d be gone in a few days, way too little time to break down any perceived walls of conceitedness to get into her pants) she was included in the social environment and even provided the luxury of having a go at the boombox with her own selection. She went back to the redhead’s car and pulled out a cassette of Upstairs At Eric’s. We were probably listening to Pyromania or 1999, both great albums in their own right, but certainly nothing tremendously groundbreaking and certainly not very hip to someone within earshot of a low-wattage college station or similarly located dance club.

Within moments of the pecking, tart synths of “Don’t Go,” some heads turned to ask “What is this?” while the bolder musical snobs looked at the strangely positioned mannequins on the cassette cover of the album. When the album was over, we probably countered with something ridiculous like Frankie Goes To Hollywood, but no matter: some creative soul (perhaps myself or the host of the party) secretly “lost” the cassette with the obvious intention of not returning it. Thankfully, liquor has a strange effect like causing people to forget things like inhibitions, panties, and cassette tapes of Upstairs At Eric’s.

From there, the cassette found its way into the car stereo of my friend’s Pontiac Firebird, where the sonic effects of the music was met with the approval under the influence of marijuana. It became an issue of 1.) either we must conceal the fact that the tape was in our possession or 2.) we must find a dubbing cassette to make a copy before returning it to its rightful owner before she left to go back east.

The first answer was hard to deal with as the red haired friend called the following day to inquire on the whereabouts of the tape. I could truthfully delay the return of the cassette since it was still in the armrest of the Firebird and, since it was summer, it may be a few days to coordinate with the schedule of the friend and the redhead.

Actually, I saw my friend on a fairly regular schedule, and by Monday, I had the cassette back but not before he had made a shitty copy of it on his dual cassette boombox; fidelity, Dolby, and the added tape hiss was not an issue with him.

I then received a couple of phone calls from party-goers who wanted to know the name of the band and if they too could get a copy made for their own collection. One of these calls was from someone who had a dubbing cassette desk in his components that could transfer the noise-reduction and do it at double speed.

Three copies were made (mine, his, and a friend of his) and we were pleased with the results. The original was dutifully provided back to the redhead in time for her to return it to her friend before she left our small town and planted the seed of Yaz among its teenage citizens.

By the following weekend, I ran across two additional people who had made third generation copies of our own, diminishing the fidelity even more, but not the enthusiasm for this electronic duo.

Upstairs At Eric’s was a strange find, particularly for a town that typically preferred heavy metal and who’s main employer was various manufacturing plants that provided high school graduates with minimal intelligence and initiative with a decent paying job until the plants eventually shut down.

The metal kids were actually fairly receptive to Eric’s trippier tracks like “I Before E (Except After C)” and “In My Room.” The chicks liked the love songs like “Only You” and “Midnight.” And, of course, the gay kids who had yet come out of the closet preferred the dance tracks like “Situation” and “Bring Your Love Down (Didn’t I).” It remains a touchtone album for me and it remains one of the best examples of 80’s British electronica today.

It also served as a precursor to gay dance music (Bronski Beat, the Clarke led Erasure, Dead or Alive) which makes the dichotomy between my hometown makeup and the fan base of a lot of these types of bands quite amusing.

One curious footnote to Yaz: My Father only demanded that I remove two music selections during family car trips, thereby securing my understanding that the driver of the vehicle is in charge of all of the controls as well. One tape was Yes’ Drama (ironically, I brought this tape because I thought the Cream-lovin’ guy would like it. We got lost, he got frustrated, and he felt this album was “distracting.” It is a shitty album. But still, let’s place blame correctly.) and the other was Upstairs At Eric’s. He told me to “Turn that shit off!” When I persisted and wanted to know why, he told me it sounded like “A guy trying to sound like a girl with a bunch of synthesizers.”

“That is a girl, Dad!”

It didn’t matter; he turned the radio on and we listed to N.P.R. instead.

A few months later, I was down at the Disc Jockey record store and noticed a strange album cover on the new releases section. It was Yaz’s second and final album You And Me Both released just before Moyet and Clarke ended their relationship together. I picked up a copy and went up to the counter to pay for it. Standing in line ahead of me was the redhead who’s friend introduced a small town to the English electronica band Yaz. In her hand was her own copy of You And Me Both and in her head she was still probably oblivious to the domino effect her friend had on a small town in Iowa the summer before.

Saturday, November 11, 2006

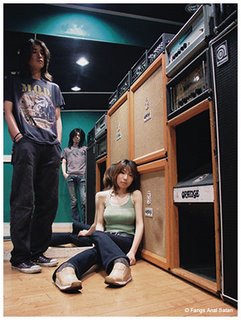

Pretty Girls Make Graves-Elan Vital

I’m late to the game on this one, but whatever, so many cds and so little money to spend. When I stumbled upon a recent release by Pretty Girls Make Graves, I remembered that I really enjoyed their debut Good Health and then I remembered that they released a second album (The New Romance) that I thought was fairly well received even though I didn’t buy it. Why not pick up the third and see where they’ve gone in the four years since Good Health?

I’m late to the game on this one, but whatever, so many cds and so little money to spend. When I stumbled upon a recent release by Pretty Girls Make Graves, I remembered that I really enjoyed their debut Good Health and then I remembered that they released a second album (The New Romance) that I thought was fairly well received even though I didn’t buy it. Why not pick up the third and see where they’ve gone in the four years since Good Health?It’s nice to hear that P.G.M.G. are trying to expand their abilities, but the question is, when do you reach the point where you’re simply reaching too far?

Elan Vital finds the band leaving ’78 Avengers-esque material and perfectly timing their age with that of the underground in ’82. And like a lot of those same underground records in ’82, there’s a large percentage of unmemorable tracks that tend to overwhelm the ones you wished you hadn’t forgotten.

There’s a few really good songs on Elan Vital (“The Nocturnal House” and the dreamy ballad “Pearls On A Plate” stand out). Unfortunately, you’ll probably forget about them in a year or two because the rest of the album is littered with a lot of half-baked ideas seemingly based on the notion that “Hey, it’s our third album so we really should have a trumpet on this track.”

As a result, the album is plagued with inconsistencies as the band tries their hand at different directions before they’ve even attempted to master the one they originally started with. Take “Parade,” which starts by asking “are you happy with what you got?” before urging the masses to “hang up their apron strings” and call their “auntie” to go marching in the streets. I’m not sure if I even have an “auntie,” but I’m positive that nobody in my family (male or female) has even owned an apron in the past half century. It’s a song better suited for a different generation and for a different band entirely. It’s also the song that got me wondering: what happened to Pretty Girls Make Graves?

Every song seems intent on starting a different approach, halfassed challenging themselves with placing the majority of the burden on the listener, particularly ones like me that at one time championed them.

Whereas before P.G.M.G. had a unique Avengers-meet-Fugazi vibe going before, they’ve managed to completely lose any sense of identity in the process of trying to find out who they want to become.

As a result, the album is plagued with inconsistencies as the band tries their hand at different directions before they’ve even attempted to master the one they originally started with. Take “Parade,” which starts by asking “are you happy with what you got?” before urging the masses to “hang up their apron strings” and call their “auntie” to go marching in the streets. I’m not sure if I even have an “auntie,” but I’m positive that nobody in my family (male or female) has even owned an apron in the past half century. It’s a song better suited for a different generation and for a different band entirely. It’s also the song that got me wondering: what happened to Pretty Girls Make Graves?

Every song seems intent on starting a different approach, halfassed challenging themselves with placing the majority of the burden on the listener, particularly ones like me that at one time championed them.

Whereas before P.G.M.G. had a unique Avengers-meet-Fugazi vibe going before, they’ve managed to completely lose any sense of identity in the process of trying to find out who they want to become.

Friday, November 10, 2006

Mew-And The Glass Handed Kites

I really want this album to be stronger than it actually is: a forgettable throwback to those halcyon days when the term “shoegazer” was somewhat novel and when bands effectively created epic swells with nothing more than feedback, guitar pedals, and a dash of studio trickery.

I really want this album to be stronger than it actually is: a forgettable throwback to those halcyon days when the term “shoegazer” was somewhat novel and when bands effectively created epic swells with nothing more than feedback, guitar pedals, and a dash of studio trickery.It’s not that I’m against “epic swells,” and Lord knows that I’ve listened to enough Spiritualized and Pink Floyd to appreciate symphonic arrangements. What I do have a problem with is a band that teases me with lush atmospheres, hinting at My Bloody Valentine the entire time, and with barely a hint of the guitar leaving Cape Canaveral’s launch pad. If you’re going to come off as a “space rock” band, then for God’s sake, leave the atmosphere and don’t forget to actually rock when you’re weightless. Mew takes their influences and somehow manages to completely devoid them of any bite. What’s left is the equivalent of leaving an opened two-liter bottle of Coke in the fridge for a week: cold, flat and with plenty of sugar.

Mew, a Danish quartet (not to be confused with a Pokeman character of the same name) released their fourth album And The Glass Handed Kites last year in Europe. Sony waited almost a year to release it domestically, and now we have an opportunity to hear what many have considered one of Denmark’s greatest exports.

It starts promising with “Circuitry Of The Wolf”; six string squalls and distorted drums setting an expectation that we may have another guitar-oriented dreamweapon. At around the 65 second mark, the first hint of a piano appears, then the first time change, and then a voice. Vocalist Jonas Bjerre appears in fine angelic form, and it’s his voice that becomes the album’s consistent focal point.

“There’s a taste that you can’t shake,” they declare in “Special” (Win). I know what they’re talking about. By the halfway mark, I was wishing Bjerre’s wings would melt; his voice is very capable while managing to be frustratingly limited within the confines of the insole of a shoegazer. Sure, the fella has range, but show me a little insight into why you’re getting worked up on every friggin’ track.

The reason I’m so hard on this album is because it has the potential to be something so much better. There are moments of brilliance: the shimmering “Why Are You Looking Grave?” (featuring J Mascis on guest vocals), the track “White Lipts Kissed” finally manages to give the listener one of the most heartfelt lines with its chorus of “I don’t cry when your silver lining shows” and much of the album’s last few tracks provide the most memorable moments. The best moment comes at the tail end of “Kites” when the music completely fades out, leaving Bjerre vulnerably pleading “Stay with me / Don’t want to be alone.” So give me another half dozen tracks like the most delicate moments in And The Glass Handed Kites and you’ve got yourself an album that ranks alongside Loveless without trying to sound like it. Until they do, there’ll be a lot of us still patiently waiting for Kevin Shields to come out of retirement and remind us all how bands content with looking at their shoes are able to achieve liftoff. Mew works best when there’s someone on the ground, securely holding their kite strings.

This review originally appeared in Glorious Noise